In preparation for a new school year, here are our staff blog picks from last year. Read on for four easy-to-use teaching tips for the writing classroom.

Tom Polk, Assistant Director, recommends Mini and Mighty: How the One-Minute Paper can Transform Your Teaching.

In this article, Tom Sura recommends using a simple index card to assess students’ understanding. He uses them at the end of each class to review what students believe was most important and any questions they have.

Tom Polk writes: “what I love about Professor’s Sura strategy is its simplicity. We often think and talk of teaching with writing as an arduous endeavor, but the one-minute paper doesn’t really require planning, time, or technology. It, however, can provide critical insight into our students’ learning while also developing their practice of reflection if used regularly. For professors who are looking for an easy way to start using writing as a pedagogical tool, the one-minute paper is a good place to start.”

Dr. Michelle LaFrance, Director, recommends Error in Student Writing: A Balanced, Developmental Approach:

Paul Corrigan encourages teachers to re-consider their marking of student errors in this piece. By reconsidering their marking, teachers can better encourage and support students’ writing development.

“Paul’s piece reminds instructors that less is sometimes more in dealing with writers at all stages of development—a prospect that is both good pedagogy and time saving for me as an instructor,” comments Michelle.

Alisa Russel, Associate Editor of The Writing Campus, recommends Placing Writing Processes on the Wall:

Here, Donald Gallehr narrates a teaching experience in which he asked students to map out their writing process and THE writing process, thereby helping students re-consider the effectiveness of their process.

“What I love about this piece, whether you follow Dr. Gallehr’s exact activity (which he details nicely for you) or whether you modify it slightly, is that it encourages explicit discussion about writing processes,” explains Alisa. “I think many of our students believe that more experienced or professional writers don’t engage a writing process – that words flow through them from on high. It’s all very mysterious. However, Dr. Gallehr’s activity forces students not only to recognize and name their own processes, but then evaluate them against other models. This way we bring the “grunt-work” of writing out of the mysterious shadows and into the light for our students to better shape their processes – and hopefully produce better papers because of it.”

Emily Chambers, Graduate Research Assistant, recommends Infographics: A Fun, Multimodal Tool for Student Thinking and Writing:

Ben Causey describes how to use infographics and even employs some of his own in this article. Ben outlines ways to use infographics in the writing classroom for pre-writing, revising, or as a stand-alone assignment.

Emily notes that “Ben describes multiple ways to use infographics in the classroom, such that they become accessible and feasible, even alongside a writing assignment or without technology. I’m excited about the ways that infographics can help students compose or revise, as well as helping them improve their technological and visual composition skills.”

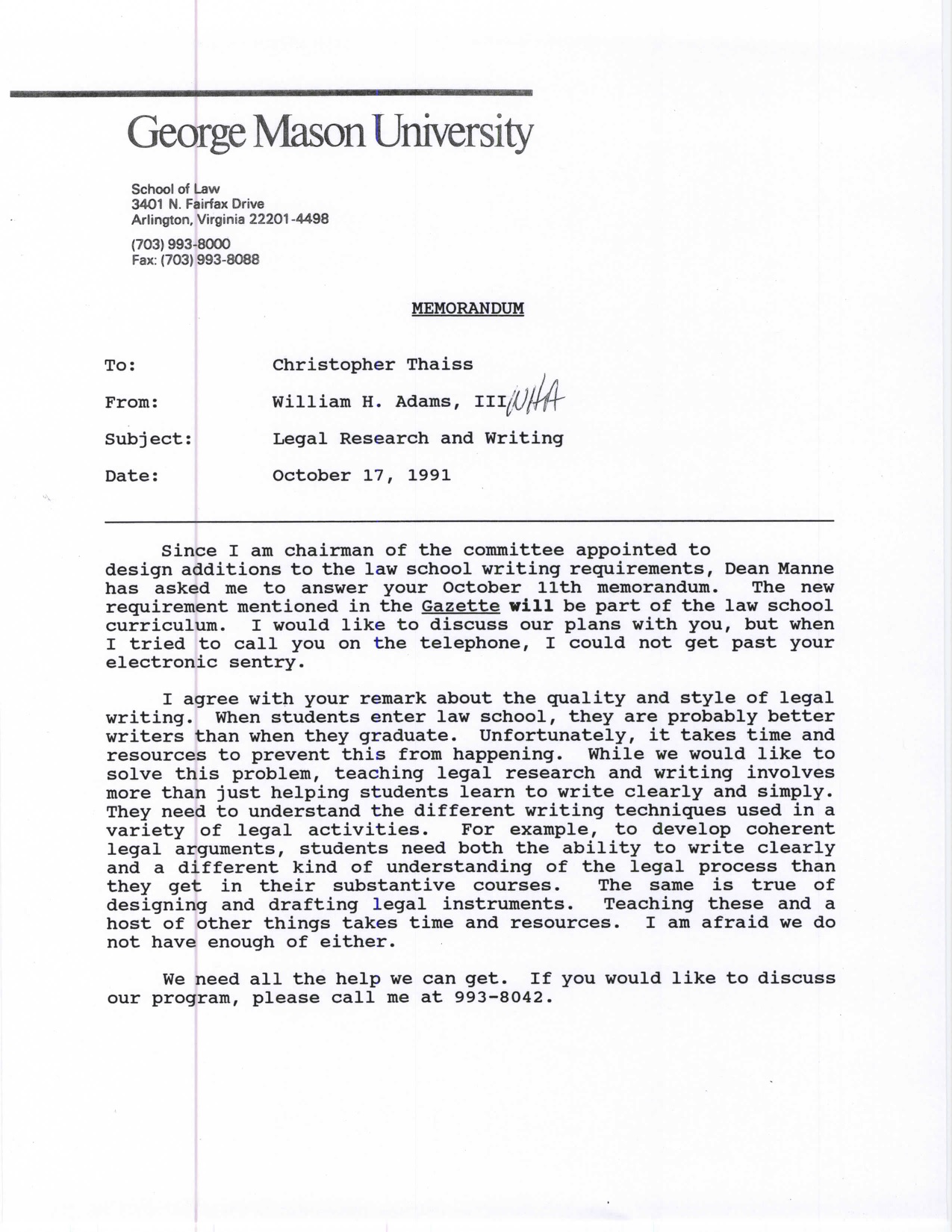

In a memo to Christopher Thaiss, WAC Coordinator, William H. Adams, of the School of Law, wrote, “They need to understand the different writing techniques used in a variety of legal activities…to develop coherent legal arguments, students need both the ability to write clearly and a different kind of understanding of the legal process.” In response, Thaiss sent Adams materials on writing principles and characteristics that work across the disciplines.

In a memo to Christopher Thaiss, WAC Coordinator, William H. Adams, of the School of Law, wrote, “They need to understand the different writing techniques used in a variety of legal activities…to develop coherent legal arguments, students need both the ability to write clearly and a different kind of understanding of the legal process.” In response, Thaiss sent Adams materials on writing principles and characteristics that work across the disciplines.

ter I have learned how to organize and explain my thought[s] more appropriately. I feel I have gotten away from the page filling method of writing. I am better able to write the necessary material to make my point and thoughts clear. Though I at one time was under the

ter I have learned how to organize and explain my thought[s] more appropriately. I feel I have gotten away from the page filling method of writing. I am better able to write the necessary material to make my point and thoughts clear. Though I at one time was under the