This piece was first published in our WAC 2015-2016 newsletter.

By Emily Chambers

Emily Chambers is an English M.A. student in the Teaching Writing and Literature program and a Graduate Research Assistant for Mason WAC. She taught sixth grade English for five years in Culpeper, VA before beginning her studies at GMU. Emily’s main interests are in teacher development and curriculum resources. She can be reached at [email protected].

Mason WAC has a rich history of supporting faculty who teach writing across the disciplines. During the 2014-2015 academic year, WAC worked with the GMU Libraries to archive over 30 years of the program’s historical documents. In the Fall of 2015, I searched through those archives for evidence of the history and work of WAC. What I found was documentation of the relationship-building work carried out across campus, by program and department faculty interested in supporting student writers at all levels. Documents reveal conversations with faculty in Nursing, Law, Psychology, Art, and more. Documents include meeting memos, reports, syllabi, student writing, and ongoing communications about course development. There are print and hand written notes from phone calls about writing contests, writing ambassadors, and other collaborations. Through these partnerships, a WAC Committee was formed in 1993 and began to define what writing across the curriculum meant. The Committee continues to do so, overseeing the approval and review of all WI courses on Mason’s campus. Here are three examples of documents in the archives:

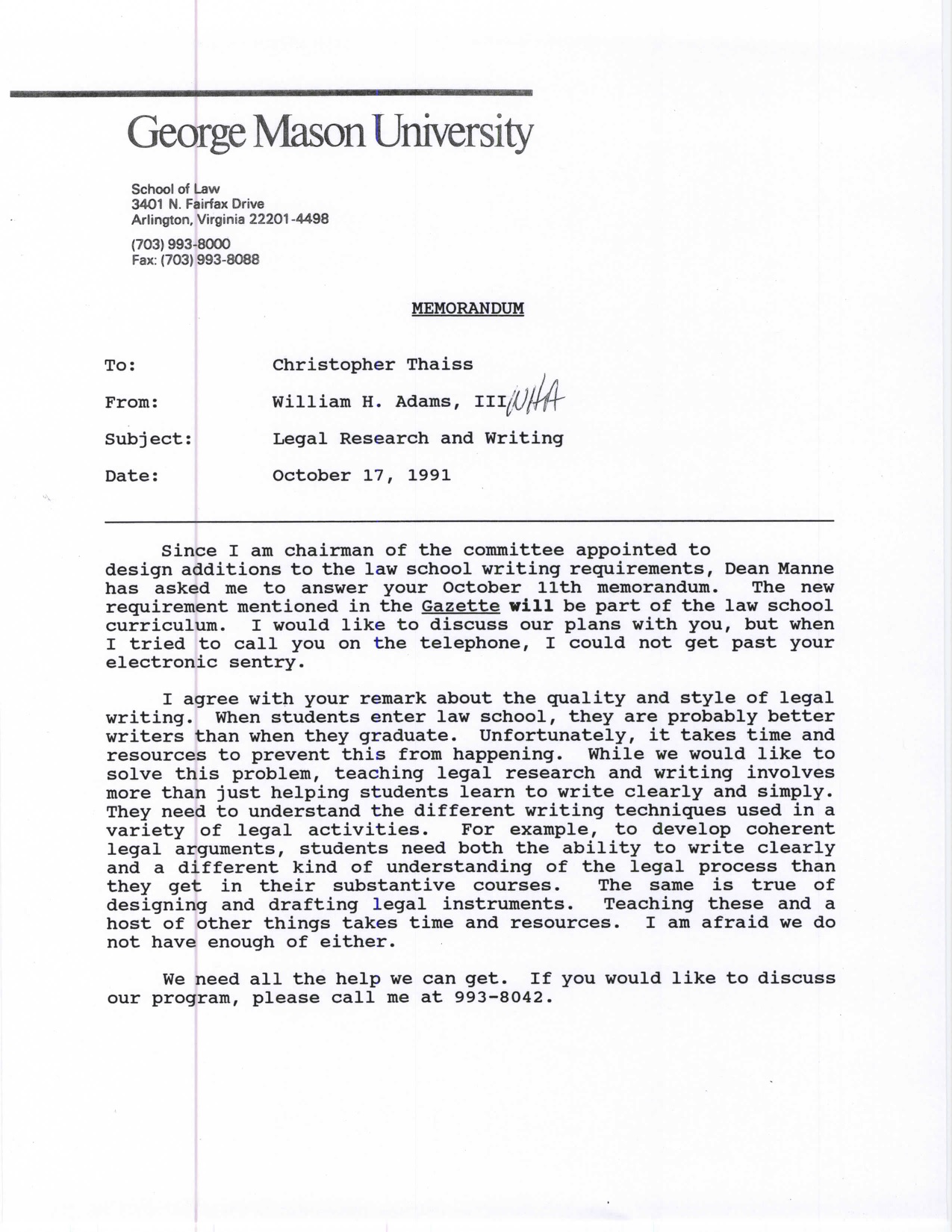

In a memo to Christopher Thaiss, WAC Coordinator, William H. Adams, of the School of Law, wrote, “They need to understand the different writing techniques used in a variety of legal activities…to develop coherent legal arguments, students need both the ability to write clearly and a different kind of understanding of the legal process.” In response, Thaiss sent Adams materials on writing principles and characteristics that work across the disciplines.

In a memo to Christopher Thaiss, WAC Coordinator, William H. Adams, of the School of Law, wrote, “They need to understand the different writing techniques used in a variety of legal activities…to develop coherent legal arguments, students need both the ability to write clearly and a different kind of understanding of the legal process.” In response, Thaiss sent Adams materials on writing principles and characteristics that work across the disciplines.

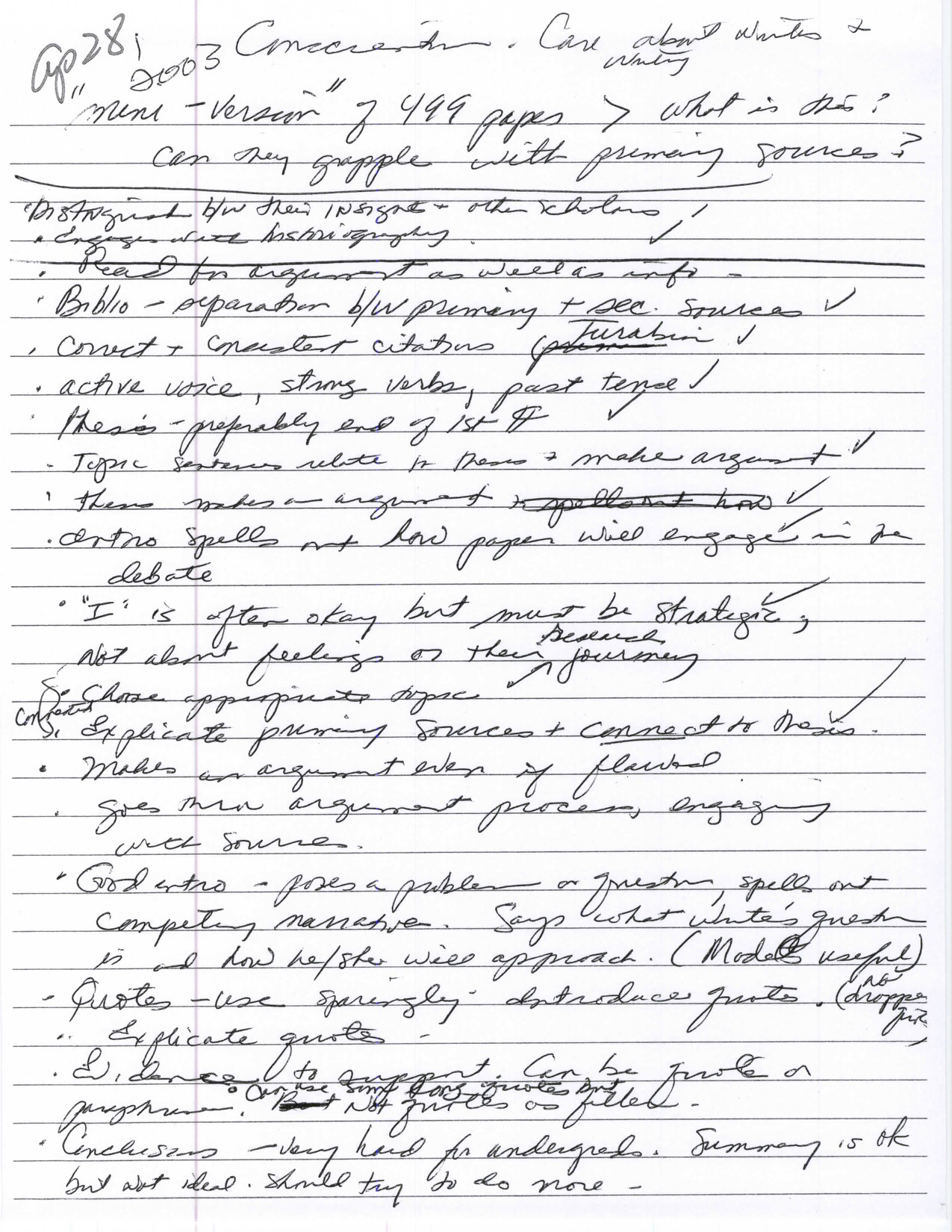

On a handwritten note from a faculty meeting, titled “’mini-version’ of 499 papers,” the author jotted down these notes:

“Intro spells out how paper will engage in the debate;

“‘I’ is often okay but must be strategic;

“Makes an argument even if flawed.”

This note shows the ongoing collaboration between WAC and faculty in the departments, as they strive to define writing expectations in the disciplines.

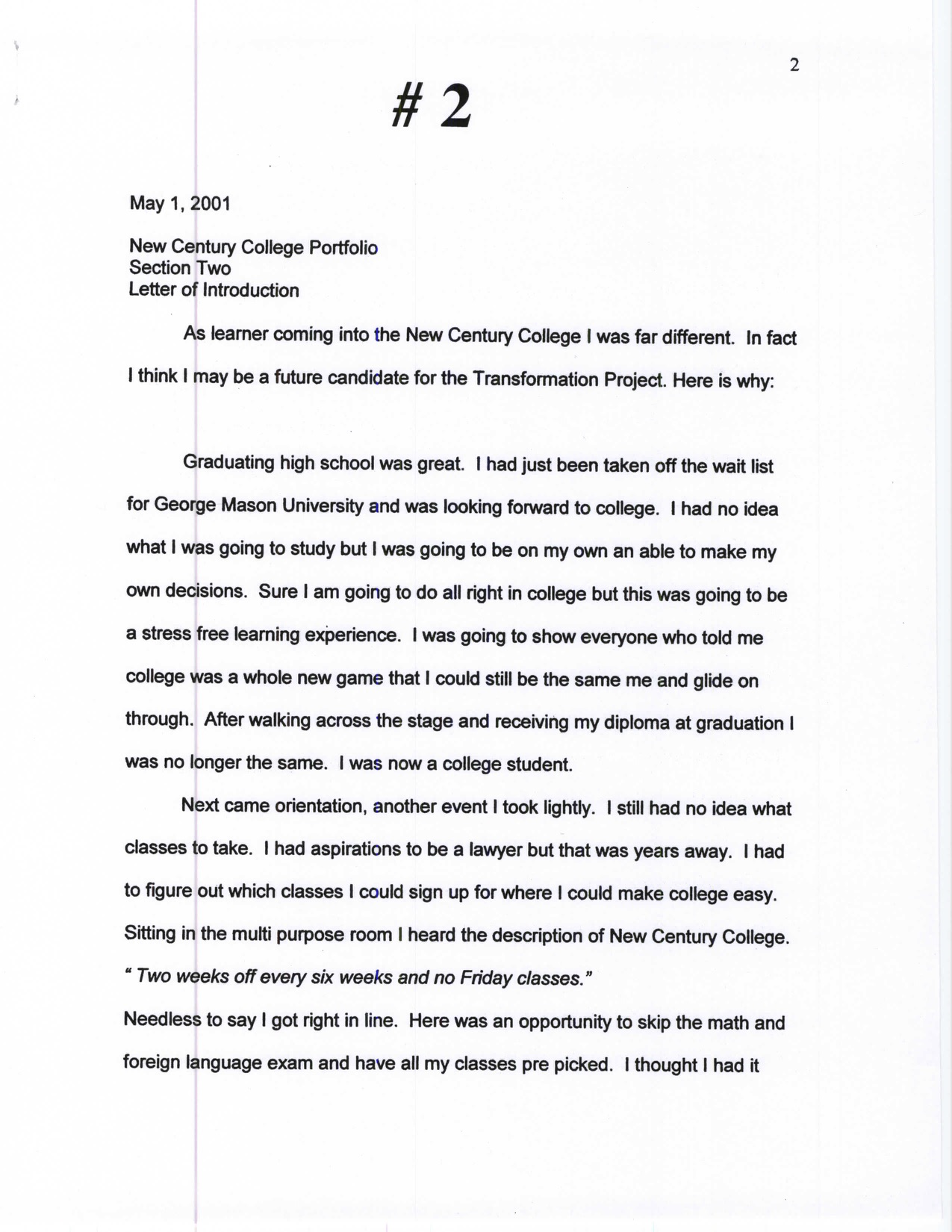

In her New Century College Portfolio reflection piece, one student writes, “As a learner I am now better able to read and write, two things that seem more basic than they actually are…As a wri ter I have learned how to organize and explain my thought[s] more appropriately. I feel I have gotten away from the page filling method of writing. I am better able to write the necessary material to make my point and thoughts clear. Though I at one time was under the

ter I have learned how to organize and explain my thought[s] more appropriately. I feel I have gotten away from the page filling method of writing. I am better able to write the necessary material to make my point and thoughts clear. Though I at one time was under the

misconception that informative writing had to be plain and straight forward, I have learned to make my writing interesting to not only the reader but also me the writer.” This student’s rich metacognitive awareness is a model for writing students, and one that WAC aims to help students achieve through WAC’s support of writing teachers.

Mason’s WAC program continues to be grounded in this rich history of relationship-building and work across the curriculum, even as it seeks new ways to support and reach writing teachers across campus and to advance the conversation about writing course pedagogy.