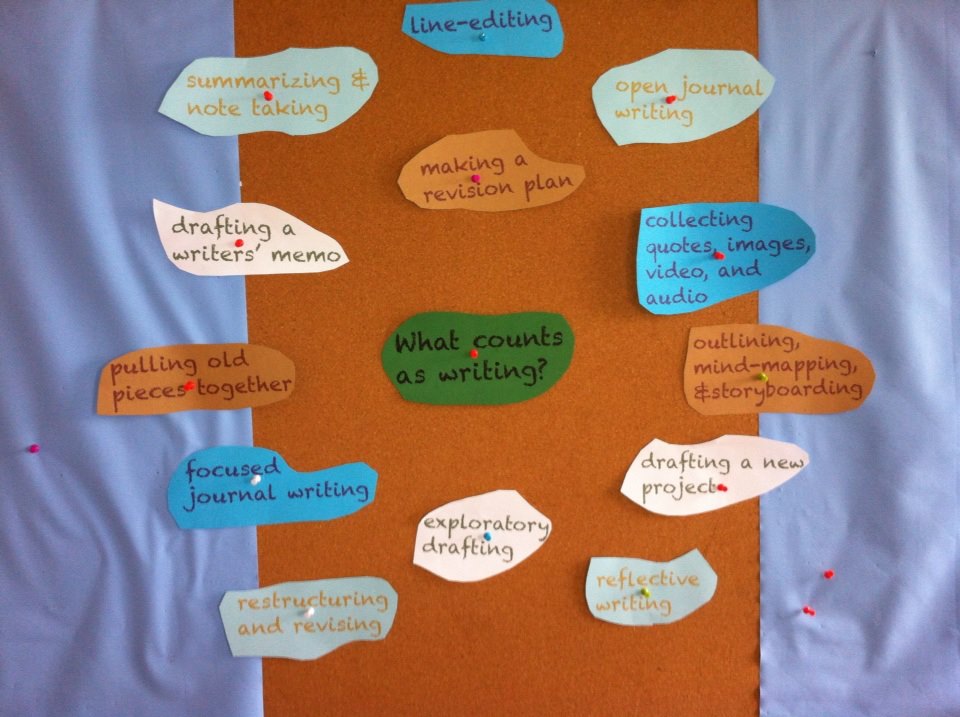

When we think about assigning writing and writing activities in our courses, we often think about it in terms of the number of words or pages we want students to produce over the course of the semester. In some cases, such as with Writing Intensive courses, we might even have a specific number of words students are expected to produce, or a program or department might require a specific number of written assignments and activities for a specific course.