by: Caitlin Holmes

Caitlin Holmes is the Assistant Director of Writing Across the Curriculum at George Mason University. She blogs regularly about teaching here at thewritingcampus.com. You can reach her via email at [email protected].

During a pre-semester meeting to discuss the QEP assessment findings of Mason’s English 302 Students-as-Scholars Program, instructors of our Advanced Composition courses went over the primary student learning outcomes (SLO):

- SLO-1, Discovery: Understand how they can engage in the practice of scholarship at GMU

- SLO-2, Discovery: Understand research methods used in a discipline

- SLO-3, Discovery: Understand how knowledge is transmitted within a discipline, across disciplines, and to the public

- SLO-4, Inquiry: Articulate and refine a question

- SLO-5, Inquiry: Follow ethical principles

- SLO-6, Inquiry: Situate the scholarly inquiry [and inquiry process] within a broader context

- SLO-7, Inquiry: Apply appropriate scholarly conventions during scholarly inquiry/reporting

What those discussions reinforced for my colleagues and me is that engagement in scholarship and knowledge transmission requires that students have advanced reading practices that often are not overtly discussed – or are sometimes presumed as proficiencies – as we work on writing competencies. Our rubric for these goals includes a category called “Research Instruction,” which states, “Course provides instruction in critical reading strategies that are appropriate to advanced reading for the rhetorical situation/disciplinary context.” While I had been actively teaching writing and argumentation skills in my first semester of ENGH 302, I had not spent as much time discussing reading strategies. I realized that this deficit was likely why some of my students struggled with finding research projects that met the requirements of my final paper: they didn’t use rhetorical reading strategies as a method to find the necessary information in the articles quickly and efficiently.

Determining how best to teach those strategies in a multidisciplinary section of ENGH 302 required both a bit of juggling in terms of my full course calendar and the development of an effective, one-day activity. I knew that I wanted to teach these crucial skills early, and I also knew that such a lesson needed to fit into my carefully scaffolded assignment sequence. Taking the particular language of the assessment rubric, I developed a lesson that would foreground both the key concepts that would be the skeleton of my course and that would integrate an overt discussion of academic reading strategies in the discipline. Rather than slowly introducing those concepts throughout the semester, I would have students read and discuss an article that provided definitions of them and that performed many of the strategies itself: Lloyd Bitzer’s “The Rhetorical Situation.”

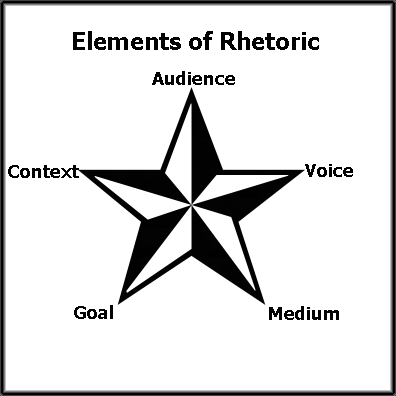

“The Rhetorical Situation” is a foundational work in rhetorical studies upon which a multitude of scholars have built both theory and pedagogy (notably, Barbara A. Biesecker and Jenny Edbauer-Rice). It defines and elaborates upon key terminology in rhetoric, such as “exigency,” “audience,” and “constraints.” As he explores these terms over the course of the article, Bitzer touches upon much of the twofold use of language that I wanted my students to learn: first, how scholarly articles are composed argumentatively and, second, how to produce within an argumentative academic framework. The article itself is difficult for junior- and senior-level students, and that level of difficulty would additionally force them to confront and address their reading strategies as a part of the exercise.

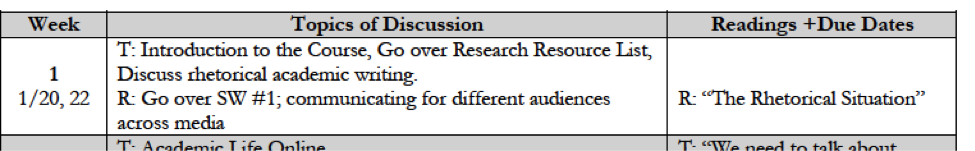

I introduced Bitzer as a reading assignment on the first day of class. Remembering José Bowen’s suggestion from last semester to have students read with purpose, I told students to read the article to try to identify the words Bitzer uses to define the rhetorical situation. “You don’t need to understand his argument perfectly,” I said. “You only need to look for the words he uses to define what ‘the rhetorical situation’ is.” Even though I verbally delivered these instructions and their reading assignment appeared on the course calendar (shown below), I also wrote the instructions on the board, as some students prefer to take pictures of my instructions to record the assignment.

I received four emails over the next 48 hours asking for further instructions on the reading. One student wrote, “We need to take notes about how he’s setting up his argument and focus on his writing correct? I don’t know why I’m having a hard time wrapping my head around this assignment but any help is appreciated.” Another emailed and asked, “You want us to just read it and be ready to share our thoughts on the piece based on all the different things we discussed today, correct? I looked on BB [BlackBoard] to see if there was some worksheet or any rubric you would like us to complete/follow but I couldn’t find anything.”

What became clear to me was that very few students had ever been told to read with purpose, and many did not know what reading for vocabulary without support materials (such as handouts or a glossary) was supposed to look like. Even with having the instructions on the board, students had been trying and struggling to apply their past reading strategies to a difficult academic text.

In our next class, I began the conversation by asking students how they read for school and wrote their comments on the board. Students volunteered a variety of approaches: highlighting, reading half then deciding if to proceed, underlining, trying to find the abstract, using the questions from the back of a chapter to find information, or just reading topic sentences. It was revealing to hear how students approached their reading assignment, and I could tell most of them were extremely frustrated with the article. I asked students to raise their hand if they felt like they understood more than 75%, about 50%, and then about 25% of the article, and most students raised their hands for 25%. What I meant to illustrate was that applying past reading strategies or just reading was not a sufficient approach to comprehending difficult scholarly work.

I then gave students a chance to produce the vocabulary that Bitzer defines in his article. As I fielded “exigence,” “audience,” and “constraints,” more words began to emerge, such as “conversation,” “argument,” “persuasion,” and “fitting response.” Students developed working definitions of the concepts that I wrote down next to their earlier reading strategies. As the descriptions grew and became more nuanced, I asked students to start looking to see if Bitzer addressed those elements himself: What was his “exigence”? Who was his “audience”? Students moved much more quickly to find the information, noting that given the level of discourse, it was likely that Bitzer was speaking to other scholars of rhetoric in order to address a particular lack in the field.

What Bitzer illustrated for my students is the sort of language surrounding both production and analysis. His language provides specific vocabulary for rhetorical analysis (i.e. “Who is the author engaging?”) and writing (i.e. “What scholarly conversation have you identified as important for your argument?”), which was the conceptual intersection I was missing in my previous class. I also initiated my students into the discourse of academic writing much earlier in the semester than I had planned, and I am hopeful that this conversation will provide students with a clear vocabulary throughout the remainder of the course.

References

Barbara A. Biescker, “Rethinking the Rhetorical Situation from within the Thematic of Différance,” Philosophy & Rhetoric, Vol. 22, No. 2 (1989): 110-30.

Lloyd F. Bitzer, “The Rhetorical Situation,” Philosophy & Rhetoric, Vol. 1, Issue 1(1968): 1-14.

Jenny Edbauer-Rice, “Unframing models of public distribution: From rhetorical situation to rhetorical ecologies,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Vol. 35, Issue 4 (2005): 5-24.