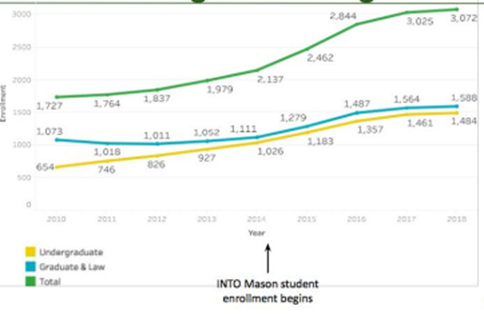

Diversity is not a buzzword anymore on Mason’s campus. It is the very keyword of our institutional identity. Recent data from Diversity, Equity and Inclusion office at Mason shows our student body consists of scholars from more than 130 nations, and members of our campus community speak at least 80 languages.

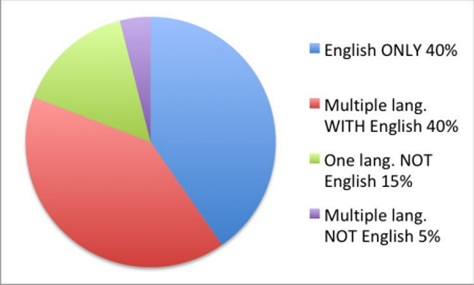

An internal review conducted by the Multilingual Academic Success Committee found that 60% of students enrolled in ENGH 302 are multilingual students and that this enrollment trend is continuing to increase both at Mason and across the nation.

Indeed, these numbers indicate the diversity at Mason is a core institutional value and belief, one that has sustained our institutional growth for decades. Yet, the numbers and statistics only tell a part of the story. Behind them lie far more complex and multilayered features of diversity.

Diversity beyond numbers

Perhaps, my story can offer a glimpse into the life of our culturally and ethnically diverse student body. My children and I are ethnically Asian Americans, and outwardly might appear homogeneous, yet our lived experiences are not at all homogeneous.

First, my children’s first language is English because they grew up in Northern Virginia and have used English at school, among their peers, and at work since they were young. However, the language they speak at home is a mixture of English and Korean. Me, I grew up in Korea and speak Korean as a first and home language, but I read, write, and speak in English as a second language for my work and study. When three of us talk to one another, English and Korean are naturally intermixed. There is no clear-cut boundary between using either English or Korean. We are not even conscious of how one language is superseded by another; we just naturally flow between them.

Yet, in my daily interaction with my children, I always feel to the depth of my bones the difference between the way my children use English and the way I do. For example, when I translate my thinking in Korean into grammatically correct English, I find my children confused or lost. In addition, their style and tone are sometimes direct when I expect them to be kind. They avoid being articulate when I believe more details will help. Conversely, they demand more elaboration when I think being straightforward resolves an issue faster.

Quite often, I feel that my translation of Korean thinking into English falls short of reaching their English minds. At other times, their English language usage is hurtful or disrespectful to me when translated into Korean. But that’s fair enough; my Korean translated in English seems sometimes redundant and unclear to them.

In the same way, our culturally and ethnically diverse students bring to our classrooms with them the above multilayered experiences with language, which are not easily visible. Their language usage flows across contexts; the form of English they use is multiple, occasionally a mix of English or other languages.

To describe this complexity and fluidity, scholars are using the term super-diversity, and our campus and classrooms are the VERY social spaces where super- diversity already exists.

Super-Diversity in classrooms and WAC

As a doctoral student in the Writing and Rhetoric program, however, I wonder if this super-diversity is being recognized in our classrooms. Since 2020, Mason as an institution has invested heavily in anti-racism and equity, most notably addressed by the ARIE initiative. In light of these efforts, WAC recognizes that it is significant to ask what the super-diversity in students’ linguistic backgrounds means for their writing in our classrooms.

There could be many unforeseen situations in which the super-diversity of our student body is not being properly honored in our classrooms. Some questions I think we can consider regarding the super-diversity in classrooms are:

- What kind of norms in our classrooms do not reflect the fluidity of students’ language use?

- What if the English translation of linguistically diverse students’ thinking or knowledge does not get across to their professor’s minds?

- What would it mean when students have strong concept knowledge of their learning but their writing does not reflect their knowledge?

- How do monolingual conceptions of language affect how we assess student learning (documented through writing)?

All these questions lead us to ask the big question:

“How can WAC embrace the super-diversity of our student body in our classrooms? “

We feel that it is urgent to explore this question now to facilitate inclusive and equity-minded philosophy in our teaching with writing.

In future posts, we will introduce some concepts that describe how language works in students’ writing and some strategies that honor superdiversity in our teaching with writing. Please stay tuned.