By: Caitlin Dungan

Caitlin Dungan is a PhD student in Mason’s Writing and Rhetoric PhD Program. Caitlin is a Graduate Research Assistant for Mason’s Writing Across the Curriculum Program, and her current research interests include fanfiction, digital media and rhetoric, online feedback practices, and participatory culture.

When scholars talk about the intersections between writing and technology, as well as how technology forms, limits, complicates or expands writing practice, we tend to overlook the fact that writing itself is a form of technology. While writing changed the world as profoundly as the wheel did, somehow the act of writing always seems to undergo cyclical scrutiny as being attacked by some new, seemingly insidious form of technology (as handwriting was by the typewriter), being changed by that technology into something worthy of being preserved, and then attacked again by whatever technological innovation comes next. As Dennis Baron discusses in A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, critics suffering from “Teknofear” consistently find ways to combat any innovation that allows for writing across new platforms. Common concerns are that technology will cause a decline in interpersonal communication, or that writing primarily in typeface, whether on a typewriter, computer, or mobile phone, detracts from the human intimacy of handwriting. Baron writes,

“The texts that writers write are the products of machinery: pencils, pens, typewriters, and now computers…In the age of mechanical reproduction, the printing press, the typewriter, and the mimeograph reproduced reading matter in quantities that scribes could never match, and now, in the digital age, computers serve to compose and disseminate both wired and wireless text in ways that are revising the definitions of reader and writer” (30).

Not only have computers complicated the ideas of “reader” and “writer” but also, as technology has become cheaper and more widely disseminated, the idea of “learner” as well.

This has not escaped the notice of professors, as the hot-button discussion of whether to embrace or limit the use of technology like laptops in the classroom continues to appear on message boards, listservs and comment sections of articles. There seems to be a lot of vitriol against the use of computers, and many feel that the drawbacks of having a laptop in class (things like decreased attention due to the distraction of the Internet) far outweigh the benefits (instant access to research). Among these concerns is the complaint that taking notes with a laptop does not produce favorable results for students. Though many students may claim that their laptop is present solely for note-taking, professors are torn about whether the notes recorded by laptop are of any use, or equivalent to notes taken by hand. Similarly, professors share anecdotal evidence that students are using their laptops primarily for non-class related browsing, which results in negative impacts on grades. As technology continues to progress, schools are spending more time focusing on keyboarding skills and technological proficiency than they are teaching script-based handwriting. Cursive is no longer a high priority in the primary school curriculum. However, some scholars feel that valuable skills, such as taking handwritten lecture notes, are in danger of becoming obsolete by the prevalence of laptops in the classroom. The larger questions under examination in this polarizing discussion are “what do we want for our students, and how do we best support them?” This blog post will take a look at a sampling of the research on using laptops in the classroom, discuss recent revelations on the relationship between laptops and student retention, and offer suggestions for how to envision using technology in your classroom so that it remains a tool and not a distraction.

Laptops vs Handwriting – The Good, the Bad, the Uncertain

In a recent study, Robin H. Kay and Sharon Lauricella noticed that research concerning laptop usage fell into five categories: “note-taking, academic activities, access to resources, academic success, and communication” (4). What Kay and Lauricella observed was that, among the studies that cumulated into these five categories, students would often state that their laptops significantly contributed to their academic success. More often than not, students reported using their laptops as their primary tool for note-taking, asserting that this method had a consistently positive impact on their academic performance. However, Kay and Lauricella describe a number of studies that found laptops to be overwhelmingly distracting, mostly in the form of personal messages and emails, social media sites, games, and streaming television websites. Do the benefits of this technology outweigh the drawbacks? Were the students correct in saying that laptops were a valuable academic asset?

In their study, Kay and Lauricella tested these assertions, mostly by amalgamating student survey responses about the same class. The answers given were not unexpected: “Students reported that note-taking was the most prevalent and important laptop activity they participated in during class. Almost two thirds of the students agreed that this activity consumed 50 to 100% of their time” (7). Some of the sample comments from students included: “‘[Using] laptops is much easier and quicker for me to take notes;’ ‘Easier to take notes than writing…;’ ‘I am able to make notes directly on the lecture slides;’ ‘I can look at other academic resources online while taking notes on the lecture; if some event I know little about is referenced, for example, I can look it up on Wikipedia’” (9). Kay and Lauricella noted that, because the class surveyed was taught in a traditional lecture-based format with frequent use of Power Point, note-taking made sense as the most frequently reported use of laptops. They pointed out that the balance between whether or not laptops are seen as primarily useful or distracting may very well hinge on the way the class is taught.

To further explore the usefulness of laptops in the classroom, Helene Hembrooke and Geri Gay decided to test the effect of unregulated laptop use on student retention. Their study had two groups of students listening to the same lecture. One group was allowed to use their laptops for unregulated browsing during the lecture while the other was asked to keep their laptops closed. Both groups were tested immediately following the lecture. Hembrooke and Gay were able to trace whether the students allowed to use their laptops were browsing for class-related content or personal entertainment by virtue of a proxy server that revealed the URLs of the students’ web browsers, which the students had agreed to use ahead of time.

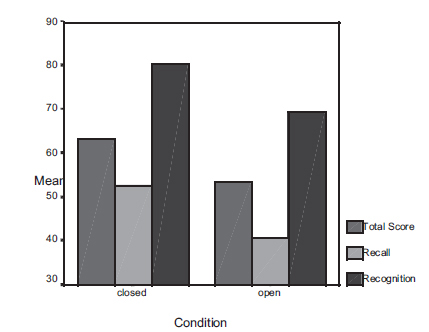

Fig. 1

The preliminary results of the study, illustrated in Figure 1, are not surprising: The students whose laptops were closed performed consistently better on the post-lecture tests (11). However, Hembrooke and Gay further analyzed the data of those with open laptops by coding the browsing “styles.” Interestingly, this recoding of the data revealed an unexpected aspect of student concentration.

“When students that spent the majority of their time on task went off task they spent an inordinate amount of time on those class unrelated pages. Those students that spent the majority of their time off task during the entire lecture spent an equivalent amount of time on class related and unrelated pages…As it turns out, ‘ontaskers’ did worse on all three measures of performance…Thus, it appears that the negative correlation between the proportion of time spent on class related sites and performance is mediated by one’s ability to monitor or balance their browsing behaviors” (11).

With this intriguing revelation, it is not necessarily the presence of the Internet or the distraction of a laptop that automatically determines whether a student will take notes effectively or suffer from retention issues. Rather, the level of engagement seems to be partially determined by their own browsing style and consistency at staying on task.

When looking specifically at laptops versus handwriting as note-taking tools, the research is somewhat divided. Though a majority of students with access to laptops report the laptop as their preferred/best tool for taking notes in class, two recent studies complicate this assertion. Bui, Myerson, and Hale conducted a study to test the results of different laptop note-taking strategies. As they discovered,

“In Experiment 1, participants were instructed either to take organized lecture notes or to try and transcribe the lecture, and they either took their notes by hand or typed them into a computer. Those instructed to transcribe the lecture using a computer showed the best recall on immediate tests, and the subsequent experiments focused on note-taking using computers. Experiment 2 showed that taking organized notes produced the best recall on delayed tests. In Experiment 3, however, when participants were given the opportunity to study their notes, those who had tried to transcribe the lecture showed better recall on delayed tests than those who had taken organized notes” (1).

As they concluded, the effect of laptops on note-taking was determined more by the participants’ working memory, and that, in fact, laptops can actually improve retention for students whose working memory is poor. By employing different strategies (transcription versus less text-heavy notes organized via outline, for example), students can adjust their note-taking to fit their own personal needs.

In their 2013 study “The Relationship of Handwriting Speed, Working Memory, Language Comprehension and Outlines to Lecture Note-taking and Test-taking among College Students,” Peverly et al. used different tools of measurement, such as “the effects of handwriting speed, language comprehension, two measures of working memory (complex span and executive attention) and an outline” to investigate the relationship between handwritten notes and student performance on class exams. As the cognitive processes behind note-taking are very similar to those required during the writing process,

“note-takers must (i) interpret and select the most important ideas, (ii) hold the information in working memory and (iii) write them down quickly before they are forgotten. Efficiency in executing (iii), a basic skill, should lessen the strain on working memory, which in turn should enable note-takers to more efficiently use higher-level processes to interpret the lecture” (115).

Again, Peverly et al. raise the issue of working memory as depictive of note-taking efficiency. Students who have disabilities, poor working memory, or who have slow handwriting speed are likely to lose aspects of the lecture as they wrestle with either physically attempting to write the lecture down, or struggle to organize the important points into an outline, thus risking inattentiveness to the current topic of the lecture while they record what was said. Additionally, students who attempt to transcribe the lecture directly will usually perform less successfully on exams due to using their cognitive processes to record instead of synthesize visual and auditory stimuli from the lectures. Peverly et al. suggest that the best practice is to provide students with an outline of the lecture prior to beginning, which will facilitate better organizational skills and allow for those with poor working memory to listen and transcribe more attentively without the need to sort through the information for the most important points while the lecture is occurring.

What these studies seem to suggest is that note-taking is not so easily dismissed as either perfectly successful via handwriting or via laptop. There are cognitive processes at work that may lead to one vehicle or another being more successful for students, depending on their learning styles. With that in mind, it may be more productive, rather than trying to advocate for or against laptop use in the classroom, to spend more time discussing how laptops can be more effectively integrated into practice for writers of different styles.

References

Baron, D. (2009). A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bui, D., Myerson, J., & Hale, S. (2013). Note-taking with computers: Exploring alternative strategies for improved recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 299-309. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

Hembrooke, H., & Gay, G. (2003). The Laptop and the Lecture: The Effects of Multitasking in Learning Environments. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 15(1), 46-64.

Kay, R., & Lauricella, S. (2011). Exploring the Benefits and Challenges of Using Laptop Computers in Higher Education Classrooms: A Formative Analysis. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 37(1), 1-18.

Peverly, S., Vekaria, P., Reddington, L., Sumowski, J., Johnson, K., & Ramsay, C. (2012). The Relationship of Handwriting Speed, Working Memory, Language Comprehension and Outlines to Lecture Note-taking and Test-taking among College Students. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27, 115-126. Retrieved March 12, 2015, from Wiley Online Library.